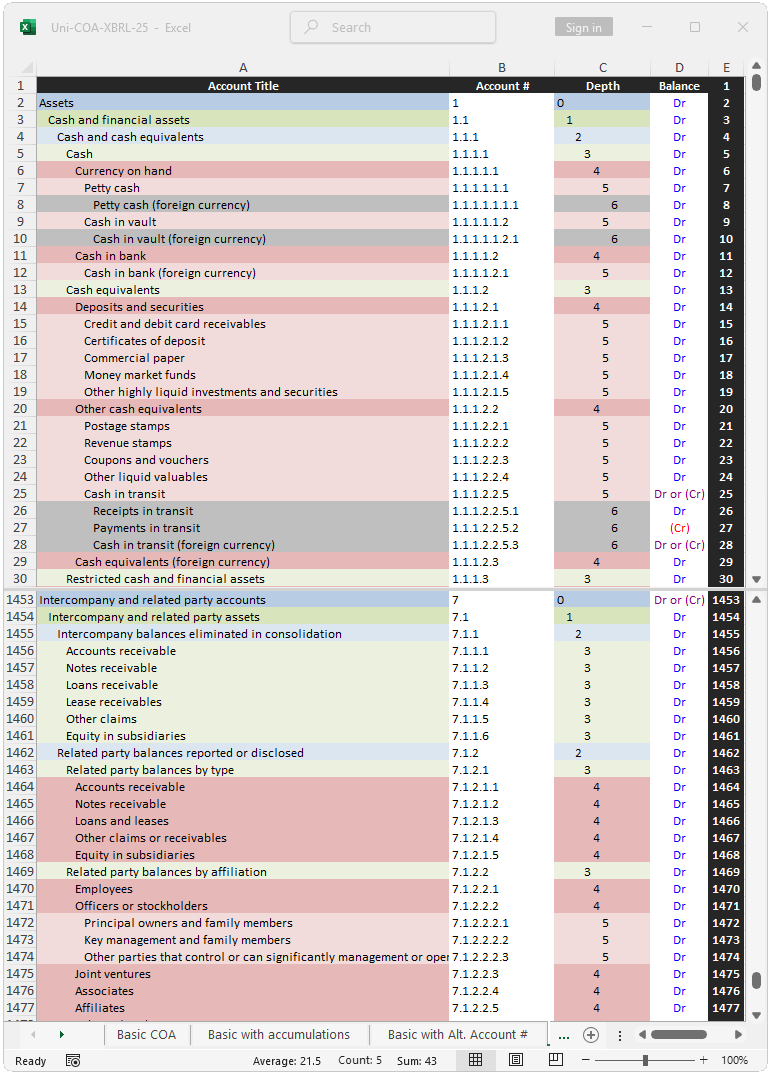

Downloads of this chart in .xlsx are available in professional view.

Professional view costs €89.90 for one year.

Professional view does not renew automatically.

Get professional view or log in.

While generally comparable, IFRS and US GAAP do not provide identical guidance.

For example, while IFRS allows low value assets to be treated as rentals, US GAAP requires all right of use assets, where the lease term exceeds 1 year, to be capitalized regardless of value. Or, while IFRS requires long-term provisions to be discounted, US GAAP does not have the same requirement for contingencies. Or, while IFRS allows development to be capitalized, US GAAP does not. And so on.

Thus, if this COA is used for dual reporting purposes, adjustments will need to be made. The same applies if it is used by a parent that consolidates subsidiaries using the two standards. For this reason, our Illustrations section outlines the most common differences between IFRS and US GAAP.

We strongly suggest reviewing the Illustrations thoroughly before attempting to use this COA for dual reporting or consolidation purposes.

This chart of accounts may be used with IFRS, US GAAP and other comparable accounting standards.

In general, there are two types of accounting standards used world-wide: legalistic and judgmental.

While the former tend to instruct accountants on the mechanics of recording transactions and events, the latter prefer discussing the conditions to be met before accountants may record transactions or events.

For example, Czech national standards (link: businesscenter) say this about recognizing revenue (CAS 19. 4.2): "the sale of products and merchandise is, on the basis of relevant documents (such as invoices), credited to the relevant account in account group 60 - Revenue with the corresponding debit made to the relevant account in account group 31 - Receivables (short and long-term) or account group 21 - Cash."

Although it is an IFRS/US GAAP advisory firm, the owner of this web site is a legal entity domiciled in the Czech Republic. As a result, it must use CZ GAAP for statutory accounting purposes.

While we do not have similar, in-depth experience with other member state accounting laws, since the Czech Republic is subject to the same EU directives and regulations as all other member states, its accounting legislation is generally comparable.

Please note: even though we have a world-wide subscriber/client base, we to not claim to be experts in any national GAAP, nor can we advise any entity on how these rules and regulations can or should be applied.

Similarly, French (link: anc.gouv.fr) accounting standard Art. 947-70 (view pdf) states: "… Les montants des ventes, des prestations de services, des produits afférents aux activités annexes sont enregistrés au crédit des comptes 701 "Ventes de produits finis", 702 "Ventes de produits intermédiaires", 703 "Ventes de produits résiduels", 704 "Travaux", 705 "Études", 706 "Prestations de services", 707 "Ventes de marchandises" et 708 "Produits des activités annexes"."

While both standards are clear on the accounts that must be used, they make no mention of the conditions to be met before these accounts are used.

In contrast, IFRS 15.31 | ASC 606-10-25-23 state: ...An entity shall recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation by transferring a promised good or service (i.e. an asset) to a customer. An asset is transferred when (or as) the customer obtains control of that asset....

While IFRS and US GAAP, are clear the condition (transfer of control) for recognizing revenue, they make no mention of the accounts to be used.

While there can be some overlap, from a COA perspective, the key issue is whether the accounting standard prescribes or does not prescribe a particular COA.

This implies that while standards set by, for example, the Financial Reporting Council (link: AcSB), the Canadian Accounting Standards Board (link: AcSB) or the Australian Accounting Standards Board (link: AASB) can generally be considered comparable to IFRS | US GAAP, the national accounting standards drafted under the EU accounting directives (apart from Ireland, which uses FRC standards) cannot.

While it may, in certain situations, be legally permissible to map a COA available for download on this web site

to a COA prescribed by a standard that prescribes a COA, it is critical that this procedure be reviewed by an expert,

professionally and legally qualified to apply that standard.

Neither this web site nor its proprietor gives any guarantee, express or implied, that the COAs available for download on this site are compatible with any accounting standard (regulation, statute, law or system) that defines and/or prescribes a COA.

Any entity, physical or legal, that applies any COA downloaded from this site in conjunction with any such accounting standard (regulation, statute, law or system), does so exclusively at his/her/its own risk.

For example, a company with petty cash and two bank accounts, would add sub-accounts:

| Assets | 1 |

| Cash And Financial Assets | 1.1 |

| Cash And Cash Equivalents | 1.1.1 |

| Petty Cash | 1.1.1.1 |

| Cash in bank | 1.1.1.2 |

| Cash in bank, account one | 1.1.1.2.1 |

| Cash in bank, account two | 1.1.1.2.2 |

| --- | --- |

A company with three customers (customer # 123, customer # 234, customer # 345), would add:

| Assets | 1 |

| --- | --- |

| Receivables | 1.2 |

| Accounts, Notes And Loans Receivable |

1.2.1 |

| Accounts receivable | 1.2.1.1 |

| Customer 123 | 1.2.1.1.123 |

| Customer 234 | 1.2.1.1.234 |

| Customer 345 | 1.2.1.1.345 |

| --- | --- |

Instead of sub-accounts, it is often preferable to add sub-classifications:

| Assets | 1 |

| --- | --- |

| Receivables | 1.2 |

| Accounts, Notes And Loans Receivable |

1.2.1 |

| Accounts receivable | 1.2.1.1 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 234 | 1.2.1.1 : 234 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 345 | 1.2.1.1 : 345 |

| --- | --- |

These sub-classification can be extended as needed:

| Assets | 1 |

| --- | --- |

| Receivables | 1.2 |

| Accounts, Notes And Loans Receivable |

1.2.1 |

| Accounts receivable | 1.2.1.1 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 100321 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100321 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 00362 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100362 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 00402 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100402 |

| --- | --- |

Sub-classification may also be used to add additional account attributes:

| Assets | 1 |

| --- | --- |

| Receivables | 1.2 |

| Accounts, Notes And Loans Receivable |

1.2.1 |

| Accounts receivable | 1.2.1.1 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 100321; due 30.Jun.2020 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100321 ; 44012 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 00362 ; due 15.Jul.2020 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100362 ; 44027 |

| Accounts receivable : Customer 123, Invoice 00402 ; due 31.Jul.2020 | 1.2.1.1 : 123 , 100402 ; 44042 |

| --- | --- |

Sub-classifications can be designated using special characters (above), alphabetical characters or other symbols (with Greek letters being popular among professionals with a finance background).

This COA uses a delimited account numbering scheme.

One of the more common questions we get: why use delimited account numbers?

While it is not strictly necessary, most accountants like numbers.

For example, instead of numbers:

We have avoided using the comma in our account numbers as it is the most common .CSV delimiter.

Although semicolons are also common (especially outside the USA), we do use this character.

Users for whom this creates a conflict with existing database systems, should replace it with a different character.

| Assets | 1 |

| Cash And Financial Assets | 1.1 |

| Cash And Cash Equivalents | 1.1.1 |

| Petty Cash | 1.1.1.1 |

| Cash in bank | 1.1.1.2 |

| Cash in bank, account one | 1.1.1.2.1 |

| Cash in bank, account two | 1.1.1.2.2 |

| --- | --- |

A company could use letters:

| Assets | A |

| Cash And Financial Assets | A.F |

| Cash And Cash Equivalents | A.F.C |

| Petty Cash | A.F.C.P |

| Cash in bank | A.F.C.B |

| Cash in bank, account one | A.F.C.B.O |

| Cash in bank, account two | A.F.C.B.T |

| --- | --- |

Any scheme that facilitates machine readability (i.e. XBRL concept names) would, from a technical perspective, be permissible.

However, to put it plainly, most accountants consider anything but numbers really, really weird.

Wouldn't a simple number, without punctuation lead to better results?

The answer is: no, it would not.

Once upon a time, one of our clients had an IT department that, for some reason, could not deal with delimitation.

Since he wanted to keep his programmers happy, he decided to eliminate the period turning this into this.

|

Cash And Financial Assets |

1.1 |

|

Cash and Cash Equivalents |

1.1.1 |

|

Cash |

1.1.2.1 |

|

Currency On Hand |

1.1.2.1.1 |

|

Petty Cash |

1.1.2.1.1.1 |

|

Cash In Vault |

1.1.2.1.1.2 |

|

Cash In Bank |

1.1.2.1.2 |

|

Cash Equivalents |

1.1.2.2 |

|

Deposits And Securities |

1.1.2.2.1 |

|

Certificates Of Deposit |

1.1.2.2.1.1 |

|

Commercial Paper |

1.1.2.2.1.2 |

|

Credit And Debit Card Receivables |

1.1.2.2.1.3 |

|

Money Market Funds |

1.1.2.2.1.4 |

|

Other Highly liquid Investments and Securities |

1.1.2.2.1.5 |

|

Other Cash Equivalents |

1.1.2.2.2 |

|

Postage Stamps |

1.1.2.2.2.1 |

|

Revenue Stamps |

1.1.2.2.2.2 |

|

Coupons And Vouchers |

1.1.2.2.2.3 |

|

Other Liquid Valuables |

1.1.2.2.2.4 |

|

Cash And Financial Assets |

11 |

|

Cash and Cash Equivalents |

111 |

|

Cash |

1121 |

|

Currency On Hand |

11211 |

|

Petty Cash |

112111 |

|

Cash In Vault |

112112 |

|

Cash In Bank |

11212 |

|

Cash Equivalents |

1122 |

|

Deposits And Securities |

11221 |

|

Certificates Of Deposit |

112211 |

|

Commercial Paper |

112212 |

|

Credit And Debit Card Receivables |

112213 |

|

Money Market Funds |

112214 |

|

Other Highly liquid Investments and Securities |

112215 |

|

Other Cash Equivalents |

11222 |

|

Postage Stamps |

112221 |

|

Revenue Stamps |

112222 |

|

Coupons And Vouchers |

112223 |

|

Other Liquid Valuables |

112224 |

Since this limited sub-accounts to nine, he then added another digit, taking this to this.

|

Property, Plant And Equipment |

1.7 |

|

|

|

|

Machinery And Equipment |

1.7.3 |

|

Machinery |

1.7.3.1 |

|

Industrial Machinery |

1.7.3.1.1 |

|

Presses, Bending, Casting Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.1 |

|

Turning, Drilling, Milling, Grinding Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.2 |

|

Laser, Water-Jet, Photochemical, Ion Beam, Plasma Cutting Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.3 |

|

Broaching, Lapping, Honing Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.4 |

|

Turbines, Compressors, Pumps And Piping |

1.7.3.1.1.5 |

|

Ovens, Autoclaves, Heaters, Boilers |

1.7.3.1.1.6 |

|

Refrigerators, Air-Conditioners |

1.7.3.1.1.7 |

|

Washing, Cleaning, Sterilization Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.8 |

|

Cranes, Hoists, Convey Belts |

1.7.3.1.1.9 |

|

Industrial Robots |

1.7.3.1.1.10 |

|

3d Printers |

1.7.3.1.1.11 |

|

CNC, Cad/Cam |

1.7.3.1.1.12 |

|

Welders, Wrenches And Other Hand Held Tools And Machines |

1.7.3.1.1.13 |

|

Jigs, Dies, Molds, Fixtures |

1.7.3.1.1.14 |

|

Other Machines And Machine Tools |

1.7.3.1.1.15 |

|

Property, Plant And Equipment |

0107 |

|

|

|

|

Machinery And Equipment |

010703 |

|

Machinery |

01070301 |

|

Industrial Machinery |

0107030101 |

|

Presses, Bending, Casting Machines |

010703010101 |

|

Turning, Drilling, Milling, Grinding Machines |

010703010102 |

|

Laser, Water-Jet, Photochemical, Ion Beam, Plasma Cutting Machines |

010703010103 |

|

Broaching, Lapping, Honing Machines |

010703010104 |

|

Turbines, Compressors, Pumps And Piping |

010703010105 |

|

Ovens, Autoclaves, Heaters, Boilers |

010703010106 |

|

Refrigerators, Air-Conditioners |

010703010107 |

|

Washing, Cleaning, Sterilization Machines |

010703010108 |

|

Cranes, Hoists, Convey Belts |

010703010109 |

|

Industrial Robots |

010703010110 |

|

3d Printers |

010703010111 |

|

CNC, Cad/Cam |

010703010112 |

|

Welders, Wrenches And Other Hand Held Tools And Machines |

010703010113 |

|

Jigs, Dies, Molds, Fixtures |

010703010114 |

|

Other Machines And Machine Tools |

010703010115 |

While this did bump possible sub-accounts up to 99, it also threw human readability out the window.

In contrast, delimitation allows infinite expandability.

For example, one of our clients, a shipper with over 200 mid-sized and 600 full-sized trucks, wanted to recognize each truck at the COA level.

While not optimal, a delimited account number does make this approach possible.

Generally, it is better to limit accounts to a group level (i.e. Delivery Vehicles), devolving individual units of account (i.e. Vehicle #1, Vehicle #2, ...) to sub-classification level.

This approach would, for example, allow adjustments such as accumulated deprecation to be recognized at a group level, rather than individual asset level, simplifying the accounting process.

Obviously, no one size fits all structure exists.

A COA should always reflect the particular needs of the particular accounting entity.

Designing such bespoke account structures is one of the services we provide.

For more information on this and our other services, please visit our services page or contact us.

|

Property, Plant And Equipment |

1.7 |

|

|

|

|

Machinery And Equipment |

1.7.3 |

|

|

|

|

Equipment |

1.7.3.2 |

|

Transportation Equipment |

1.7.3.2.1 |

|

Vehicles |

1.7.3.2.1.1 |

|

Trucks |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1 |

|

Light Duty Trucks |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1 |

|

Light Duty Truck |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 1 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.1 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 2 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.2 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 3 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.3 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 4 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.4 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 5 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.5 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 6 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.6 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 7 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.7 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 8 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.8 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 9 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.9 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 10 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.10 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 11 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.11 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 12 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.12 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 13 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.13 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 14 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.14 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 15 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.15 |

|

Light Duty Truck # etc. |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.etc. |

|

Light Duty Truck # 245 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.245 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 246 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.246 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 247 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.247 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 248 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.248 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 249 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.249 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 250 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.250 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 251 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.251 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 252 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.252 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 253 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.253 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 254 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.254 |

|

Light Duty Truck # 255 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.255 |

|

Heavy Duty Trucks |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.2 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 1 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.1 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 2 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.2 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 3 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.3 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 4 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.4 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 5 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.5 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 6 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.6 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 7 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.7 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 8 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.8 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 9 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.9 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 10 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.10 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # etc. |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.etc. |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 650 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.650 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 651 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.651 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 652 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.652 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 653 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.653 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 654 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.654 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 655 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.655 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 656 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.656 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 657 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.657 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 658 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.658 |

|

Heavy Duty Truck # 659 |

1.7.3.2.1.1.1.1.659 |

Finally, after much gnashing of teeth, the IT department found is was possible to adjust the company’s accounting software to deal with periods.

As anyone who regularly deals with IT professionals eventually realizes, the seemingly impossible can become possible if management shows steely resolve and brings the full force of its decision making authority and budgeting power to bear.

Ours is not the first web site to number its COA using periods.

Canadian Statistics (link: statcan) has been using this format since at least 2002.

And no, we did not copy it from them. We found this COA on the internet while doing research on how different countries approach the issue of national charts of account.

Everyone lived happily ever after.

This COA does not make a current/non-current distinction.

An item's current or non-current status is a disclosure rather than recognition issue since many items (investments, loans, receivables, inventory, accruals, payables, etc.) can be either current or non-current.

Consequently, it is more systematic to structure accounts on an order of liquidity basis, devolving an item's current/non-current status to a sub-classification level (see: Current/Non-current COA).

Under IFRS, companies may use either an order of liquidity or current/non-current balance sheet format.

Under US GAAP, companies are obligated to use a current/non-current balance sheet format.

Under US GAAP, companies are obligated to use a current/non-current balance sheet format.

Under IFRS, companies may use either an order of liquidity or current/non-current balance sheet format.

This COA includes both nature and function of expense accounts.

From an accounting perspective, a nature of expense classification scheme is more practical. In addition, ASU 204-03 (ASC 220-40-50-6) updated disclosure guidance to include nature of expense items in the footnotes.

Employee benefits are a good example.

Assume a very simple company with three employees (one in production, one in sales and one in administration) which it compensates in three ways: hourly wage, salary plus commission and monthly salary. Associated with these costs, it also incurs: social security and health insurance.

As each cost has a different measurement basis, it would be reasonable to use three direct payroll accounts : Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1 (hourly measurement), Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2 (monthly measurement), Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3 (measured by sales amount), and two indirect accounts: Social Security 5.1.2.1.4.1 and Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2 (whose measurement is derived from the direct compensation amounts).

If the company decided to structure its accounts by function instead, it would need:

In Cost of Sales: Wages 5.2.1.1.2.2.1, Social Security 5.2.1.1.2.2.2 and Health Insurance 5.2.1.1.2.2.3.

In Selling Expenses: Sales Salaries 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.1, Sales Commissions 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.2, Social Security 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.3 and Health Insurance 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.4

In General and Administrative Expenses: Salaries 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.1, Social Security 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.2 and Health Insurance 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.3.

The better approach is thus to use nature of expense accounts for day-to-day recognition and measurement, in that these would be mapped to the function accounts for disclosure at the end of each period.

For an example see: Nature of expense, function of expense.

Assume XYZ company recognized period direct compensation costs of currency unit 1,000,000. In addition, it incurred social security tax and health insurance costs at rates of 30% and 10% respectively (for simplicity, also assume that production wages are expensed as incurred rather than being capitalized to inventory).

At the end of the accounting period the balances on the employee benefit (nature of expense) accounts were:

Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1: CU400,000

Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2: CU400,000

Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3: CU200,000

Social Security Tax 5.1.2.1.4.1: CU300,000

Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2: CU100,000

XYZ next determined that its production workers spent 90% of their time on production and 10% on repairs and maintenance, in that 40% of that maintenance was performed on delivery equipment. XYZ also determined that 25% salaries were paid to sales staff with the remainder paid to administrative workers, split 60%/40% between office staff and officers.

To prepare its (function of expense) financial report it allocated:

Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: CU384,000 and Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU16,000

Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2 to accounts: Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 5.2.2.1.1.1.1: CU 100,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: CU180,000.00 and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: CU120,000

Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3 to account Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 5.2.2.1.1.1.1: CU 200,000

Social Security Tax 5.1.2.1.4.1 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: CU115,200, Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU4,800, Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 90,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: CU54,000, and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: CU36,000

Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: CU38,400, Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU1,600, Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 30,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: CU18,000, and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: CU12,000

Besides a simpler account structure, this approach also allows individual expense to be recognized, day-to-day, by relatively inexperienced staff, while the period end allocations can be performed (supervised) by personnel well versed in the nuances of IFRS and US GAAP guidance

Similarly, as many national GAAPs prefer or prescribe nature of expense recognition, this approach works well at local subsidiaries of (especially) US based companies, that the day-to-day accounting can be performed by local staff (accountants trained in the local GAAP), while the period end adjustments can be performed by reporting specialists (staff trained in US GAAP and/or IFRS).

Obviously, since knowledgeable does not necessarily require presence, the local accounting staff can perform their tasks locally, while the reporting specialists can perform their tasks in close proximity to the management responsible for the final reports.

From a reporting perspective, a function of expense scheme yields better results.

Assume two comparable companies present the (absolute) minimum (operating) information required by IFRS in both expense formats:

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Cost of sales |

60 |

40 |

|

Gross profit |

40 |

60 |

|

Administrative expenses |

30 |

50 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Material |

10 |

10 |

|

Employee benefits |

50 |

50 |

|

Services |

10 |

10 |

|

Depreciation |

20 |

20 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

If the objective of financial reporting is to allow investors to make capital allocation decisions, the first format succeeds while the second fails.

Not that a nature of expense P&L doesn't have a use.

Assume two otherwise comparable companies report the following results:

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Material |

30 |

10 |

|

Employee benefits |

30 |

50 |

|

Services |

10 |

10 |

|

Depreciation |

20 |

20 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

From the perspective of a taxation authority, it is fairly obvious that ABC would be a much better candidate for an tax audit, since the likelihood of, for example, non-tax deductible expenses being misclassified as tax deductible in material is higher than in payroll.

For this reason, nature of expense P&L statements are often required in countries where national GAAP is used as the basis for tax reporting and is likely the major (unwritten) reason why IFRS allows nature of expense only disclosures while US GAAP does not.

As IFRS is international, it must be acceptable to all countries even those that use IFRS for domestic tax reporting purposes.

In other words, even though the IFRS conceptual framework states that the objective of IFRS is to serve those providing resources to the entity, the IFRS foundation would like to see IFRS applied worldwide.

CF 1.2: The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions relating to providing resources to the entity. Those decisions involve decisions about:

(a) buying, selling or holding equity and debt instruments;

(b) providing or settling loans and other forms of credit; or

(c) exercising rights to vote on, or otherwise influence, management’s actions that affect the use of the entity’s economic resources.

To make this possible, IFRS must provide guidance acceptable to the governments ratifying IFRS for use in their jurisdictions even when those governments use IFRS to fulfill objectives other than capital allocation.

In contrast, as the FASB's priority has always been for its guidance to allow investors to make capital allocation decisions, a function of expense classification scheme has always been the only option US GAAP.

A combined approach leads to the best results.

Assume two comparable companies present basic (operating) information in a combined format:

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Direct material |

10 |

10 |

|

Direcrt wages |

30 |

10 |

|

Depreciation |

20 |

20 |

|

Cost of sales |

60 |

40 |

|

Salaries |

20 |

40 |

|

Services |

10 |

10 |

|

Administrative expenses |

30 |

50 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

While an investor will likely reach a conclusion similar to the function only approach above, a combined approach allows a more through analyses, especially if a granular expense breakdown is disclosed in the footnotes.

Unfortunately, unlike US GAAP, IFRS guidance does not necessarily lead to this result.

The FASB's XBRL (link) requires function based classification:

Cost Of Goods And Services Sold

Selling And Marketing Expense

General And Administrative Expense

Within each function, it then sub-classifies expenses by nature, for example employee compensation:

Cost Direct Labor

Sales Commissions And Fees

Labor And Related Expense

Under IFRS, companies may present a profit and loss statement classified by nature only.

Even when they decide (as most do) to present a function of expense P&L, the information is presented in two separate lists, making it nearly impossible to allocate, for example, employee benefits to functions like cost of sales or administration, a problem compounded by the general lack of granularity in IFRS reports.

In a recent paper, the IASB staff, among outer findings, noted:

(a) At the April 2018 ASAF meeting, we heard from some ASAF members that entities interpret paragraph 104 of IAS 1 as a requirement to provide only some selected amounts by nature, mainly those mentioned by IAS 1 (ie depreciation and amortisation expense and employee benefits expense).

Update: February 2025.